A Column for Global Readers

Historiography is a selective lens. What survives in writing is only a fraction of what truly lived. Civilizations paint their origins with symbols, migrations, and improbable encounters — yet occasionally, myth and history stand so near each other that one begins to echo the other.

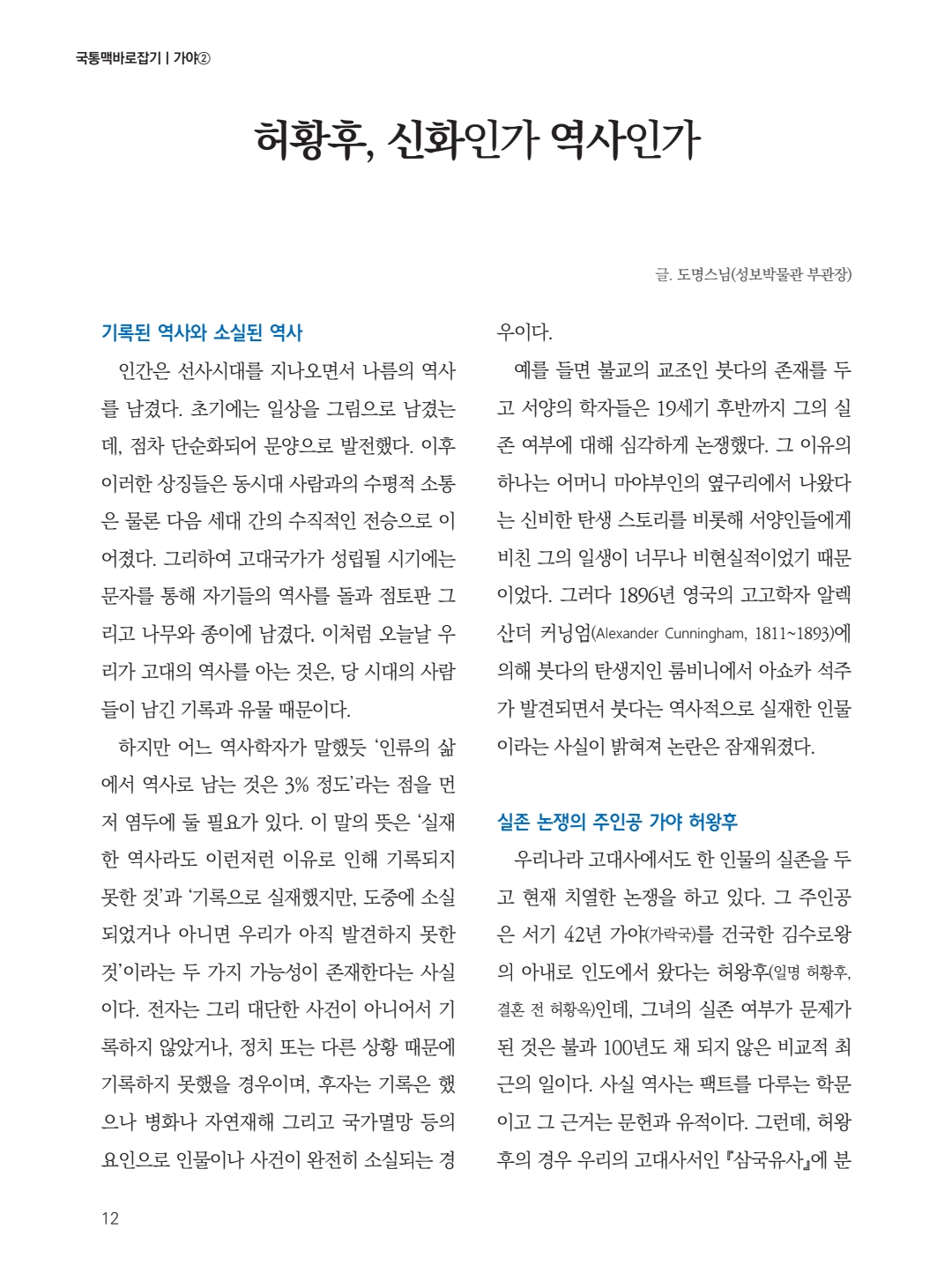

The story of Heo Hwang-ok, an Indian-born queen said to have crossed the ocean to marry King Suro of Gaya in AD 48, rests precisely in that delicate territory.

For centuries, Korea acknowledged her not as legend but as ancestry.

Today, over six million Koreans — primarily the Gimhae Kim and Heo clans — trace direct lineage to her name.

Yet modern academia hesitates. Was she real, or culturally constructed?

Are we reading memory, mythology, or a hybrid of both?

▪ When Written Records Fade, Silence Is Mistaken for Fiction

Historians estimate that less than 3% of ancient human events were ever recorded. Much was never inscribed, more was lost, and some still sleeps underground. Thus, absence of proof is not proof of absence — merely the reality of fragile archives.

This same silence once surrounded Gautama Buddha. Western scholars debated his existence until 19th-century archaeology finally uncovered Lumbini, forcing the academic world to accept what tradition had always preserved.

History, it seems, can be factual long before it becomes provable.

▪ Gaya, India, and an Ancient Maritime Crossing

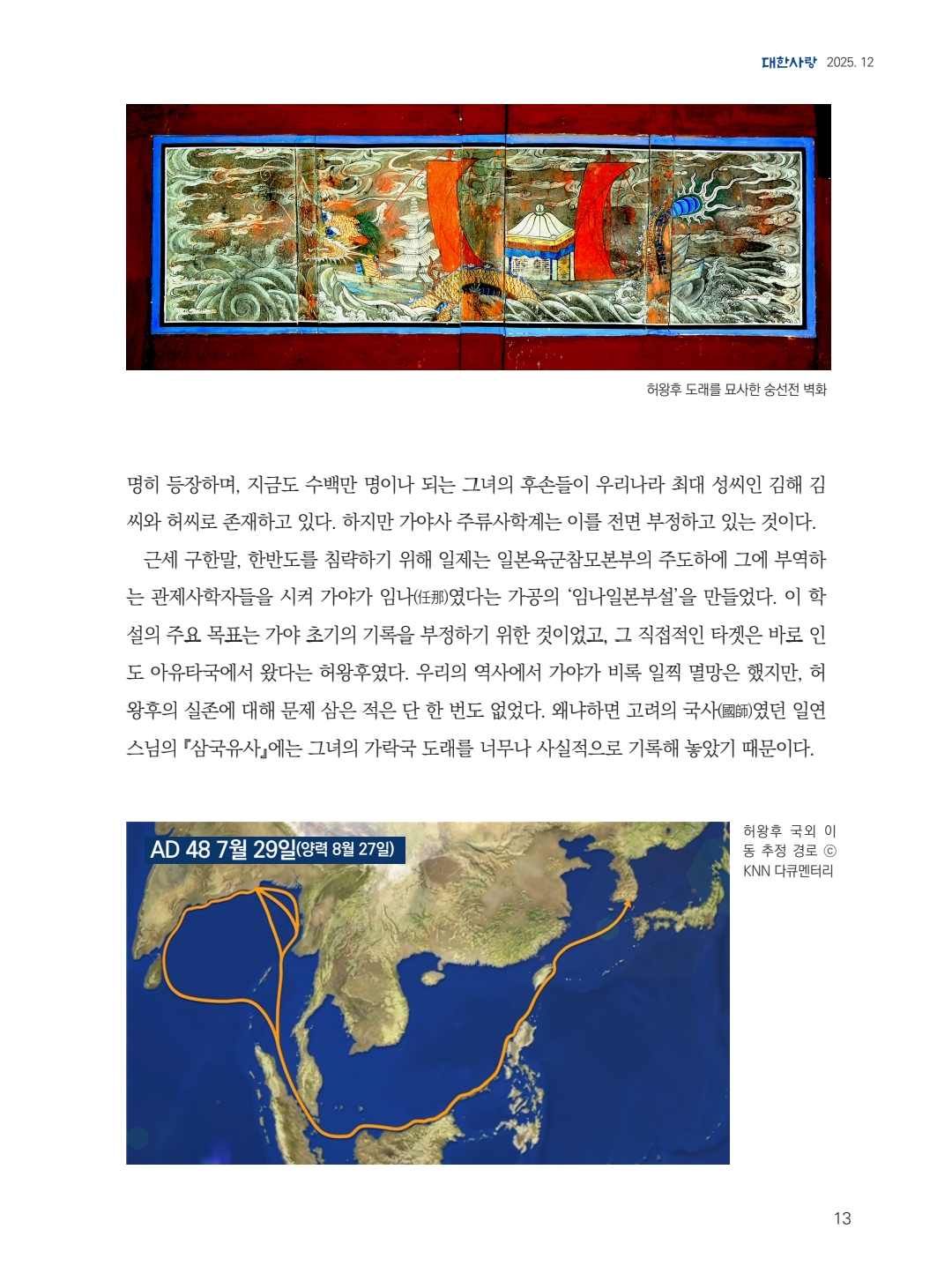

Samguk Yusa and Garakgukgi — two cornerstone Korean sources — describe Heo Hwang-ok sailing from India across the Indian Ocean and South China Sea to Gaya.

The text records:

> She brought stones for protection, arrived by divine calling,

and became the first queen of Gaya.

Colonial-era Japanese scholars dismissed this as myth because acknowledging early Gaya maritime sophistication challenged their imperial narrative. Myths were politically convenient; erasure even more so.

However, geographical traces survive today like fingerprints:

Jeonsan-do • Jupo • Palmosan • Okpo • Geomado

— mapped along what tradition calls Heo Hwang-ok’s Wedding Route.

Toponyms are cultural fossils. They rarely persist without origin.

▪ Stones That Crossed the Sea

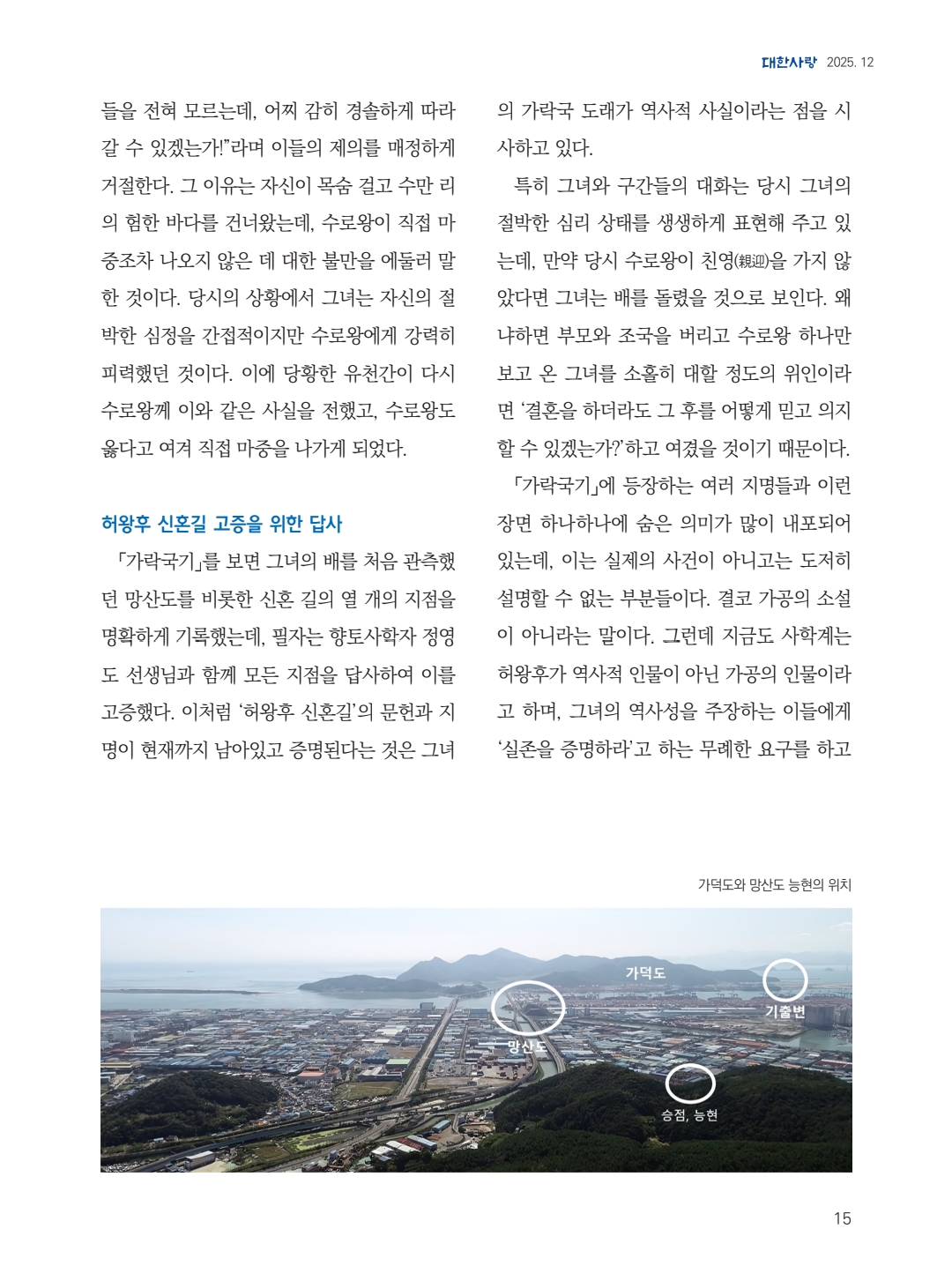

One of the most debated artifacts is the Pa-sa Stone Pagoda in Gimhae, said to be built from stones she carried from India. Critics claimed the stones were local — until 2019, when scientific analysis suggested geological traits not native to the Korean peninsula.

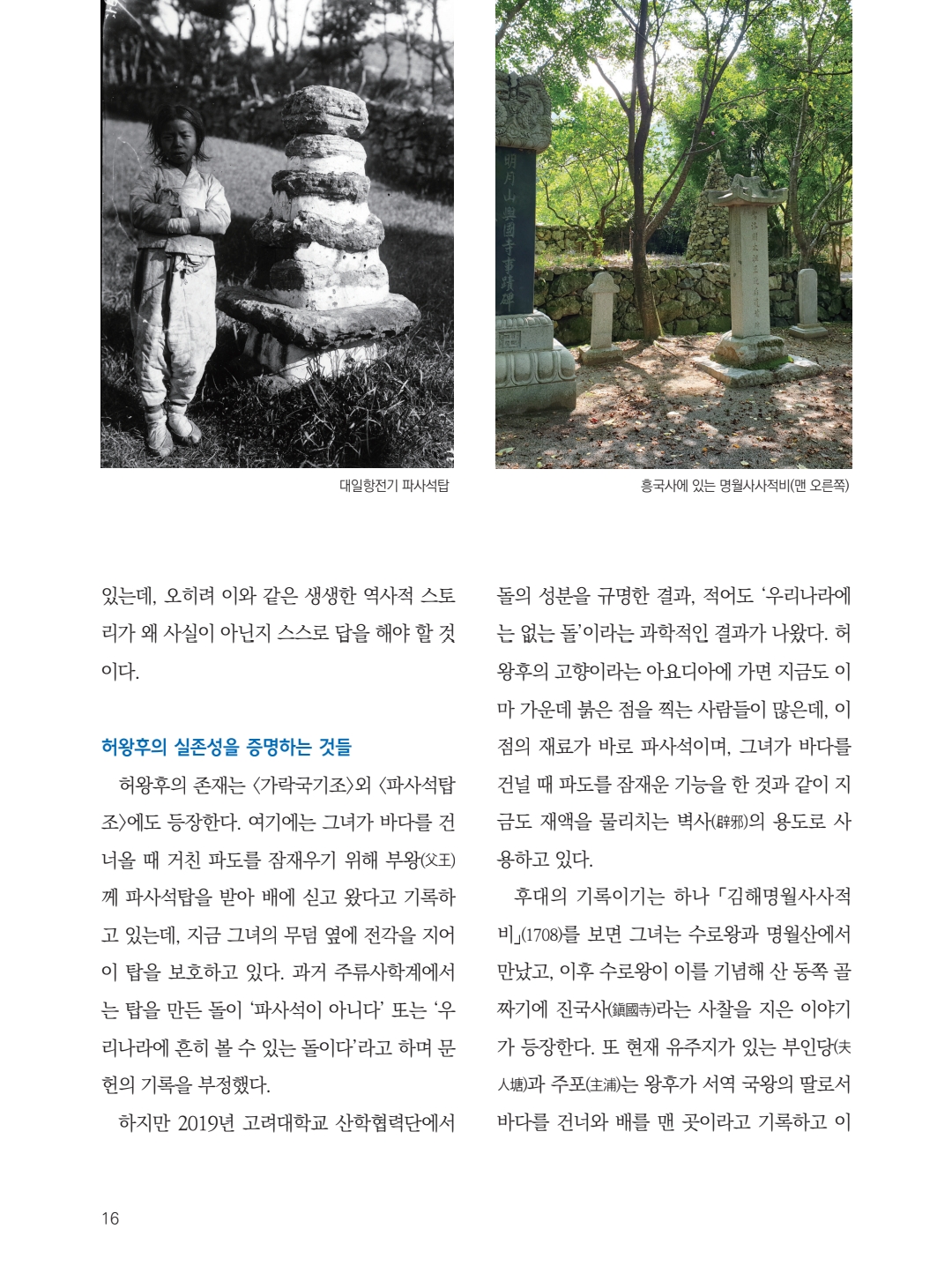

Later memorial inscriptions (1708), genealogical records, and royal tomb steles continued to preserve her name through dynasties.

In other words, history remembered even when historians did not.

▪ Myth and Person, or Person Made Mythic?

Columnists must live where scholars hesitate. If Heo Hwang-ok never existed, we must explain the persistence of her memory across 1,900 years, the survival of lineage, place names, monuments, pagodas, and ritual calendars.

Myth alone rarely sustains so stable a footprint.

If she did exist, then Korea and India shared trans-oceanic contact long before Europe imagined Asia connected. It reframes maritime history, gender roles in diplomacy, and the scale of ancient navigation.

It suggests the world was global before we called it globalization.

▪ The Columnist’s Judgment

Heo Hwang-ok may be mythologized —

but mythologized people are usually people first.

Civilizations do not invent ancestors without purpose,

nor do lineages endure without seed.

The debate will continue, as any living history should.

But a fair reading for global audiences may be:

> She was likely real — and later elevated into legend.

Not less believable, but more meaningful.

Whether queen, voyager, or symbol of exchange,

Heo Hwang-ok expands Korea’s ancient story beyond borders,

carrying across oceans a reminder:

🔸 Some histories are whispered longer than they are written.

🔸 Memory is also evidence.

'역사글' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 📌 〈제국의 그림자와 문명의 이동 — ‘제3의 고구려’와 로마의 계승 사슬을 비교하다〉 (1) | 2025.12.06 |

|---|---|

| 📌 〈로마 ↔ 고구려 계승 도식〉을 통해 본 문명 이동의 법칙 (0) | 2025.12.06 |

| 〈Carsar ‧ Gaiser ‧ Dangun ‧ Dingir ‧ Dangol〉 단군에서 세계로 뻗어나간 유라시아 음운사의 비밀 축 (0) | 2025.12.03 |

| BCE 9C–BCE 3C: Reconstructing Coree’s Forgotten Rings (0) | 2025.12.02 |

| 🌏 연개소문 vs 당태종 — 강소성까지 이어진 대륙 추격전 (0) | 2025.12.01 |